Here is a bit of calculus in dimension q. I use the letter q and not d for the dimension as we will use the exterior derivative d later. Multivariable calculus is very similar to single variable if one uses multi-index notation like or

or

or

for partial derivatives or

for the volume form. As for the Gamma function

, for the following, one has only to see

and

(which follows from making the substitution

to

which we all know from the “Gifted” movie). Since

follows from the definition and integration by parts, we know all the values

and

,

etc. With all this notation, the multi-variable Taylor formula looks like in single variable

for nice functions like polynomials. Using this one can reduce the problem to average a function

over a ball B or a sphere S (of radius h) to the cases

or

. One can restrict to the sphere because of the obvious

. As for the case

where one computes the volumes of balls. One can use reduce the computation to

as the volume of the q-ball of radius h in general is just

. As for the computation of the unit q-ball volume

and unit q-sphere volume

, use the recursions

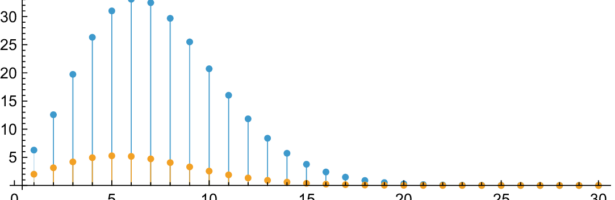

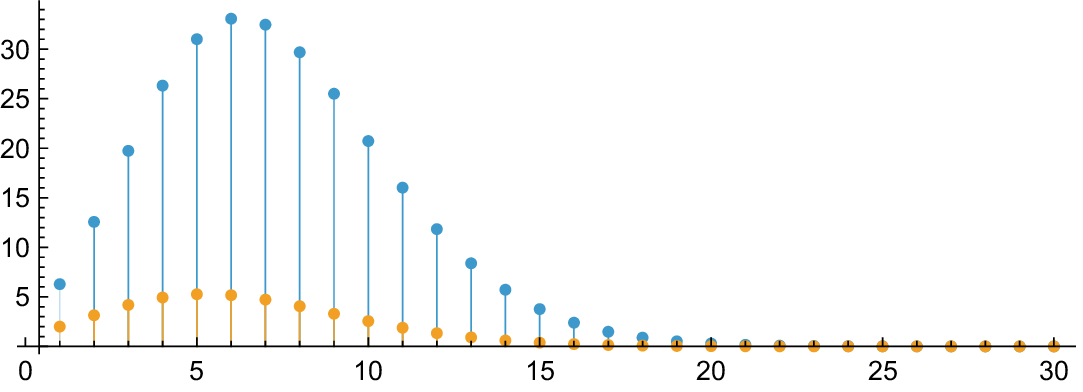

and start with B(0)=1,S(0)=2. The smallest values are (1-sphere means circle, 2-sphere means sphere in 3D, 3-sphere means sphere in 4D): the first 4 values for

are

. The first 4 values for

are

. Here is the recursion as the following one- line code in Mathematica: (see also this document [PDF] from Math 22 taught in 2018):

B[q_] := S[q-1]/q; S[q_] := 2Pi B[q-1]; S[0_] := 2; B[0_] := 1; S[100] The upshot of the talk today was that one can express spherical or ball averages using Bessel functions if using a Dirac operator, a square root of the Laplacian. This in the same time also extends the sphere averages to all differential forms and see that it is a bounded operator . With the deformed “quantized so to speak” exterior derivative, the “differential forms” do not need to be smooth any more. Any quantum wave can be “differentiated”. For example, if A is a 1-form (an electo-magnetic potential) that is only measurable, not even continuous, or for heavens sake differentiable, then F=dA does not make sense using the exterior derivative, but works for elements in the Hilbert space and in a Coulomb gauge, the Maxwell equations

latex L^2$ random variables. Why is this nice? It solves one of the programs I pursued early on to push calculus from a highly asymmetric situation with smooth functions (where the dual are distributions) not only to the continuous situation, where the dual are measures, but to Hilbert spaces, where the space is self dual. In a Hilbert space there is duality between objects and dual objects. In the classical de Rham story, there is a large asymmetry as the dual of differential forms are de Rham currents and so distributions. [We every summer get reminded about de Rham because he liked to hike also in the Baltschieder valley in Switzerland. See “Tracing Jean Piaget and Georges de Rham” from 2014. You see de Rham hiking there in this photo. See a short about the walk the Baltschiedervalley from 2025. ]

This current work is a continuation of a program, I started 15 years ago and started to pick up again this winter. It is motivated by wave front geometry. Calculating on wave fronts rather than locally using derivatives will have lots of nice consequences. One can on any Riemannian manifolds have a derivative which just averages all signals in distance h away (on the wave front and h does not have to be small!) As for larger h, the derivative goes in sie to zero, one will have some threshold after which one can define a symplectic map on the squared Hilbert space H x H which interpolates a wave equation. In the limit h to 0, one recovers the usual de Rham calculus and cohomology. For most h, we have the same cohomology,but much nicer discrete time wave dynamics which resembles more a “cellular automata map” than a partial differential equation. Nothing is discrete here however. This is classical analysis, but we have some quantum nature in the sense that we do no more use differentiability any more. The Dirac operator is bounded. Classical harmonic functions are still harmonic but depending on h, we sometimes have more harmonic functions.

This topic matches also a bit the fact that this semester, I teach probability theory. It is there an interesting task to comput expectation, variance etc on probability spaces that are balls or spheres. In the first homework for example, we asked for the probability that a data set of q points in is in the unit ball in dimension q.