If P is a light source on a cube we can look at , the wave front. Every point

of this wave front can be assigned a group element, the rotation which is needed to rotate the initial Frenet frame at the start to the frame at time t. Whenever a geodesic crosses an edge of the cube, the group element gets updated and gets multiplied by a rotation by 90 degrees about one of the coordinate axis. The group G is the rotation symmetry group of the cube. It has 24 elements as you can place the cube on one of the 6 faces and turn in one of 4 angles. The group G is isomorphic the symmetry group

as the permutation representation given by the permutations of the 4 space diagonals is faithful. The group can be generated by two rotations A, B and the corresponding Cayley graph has diameter 4. We can write every group element as a word of length 4 or less like g=ABBA or

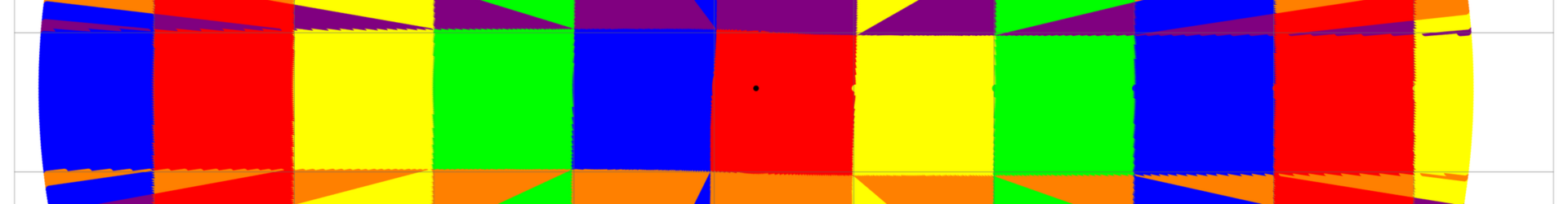

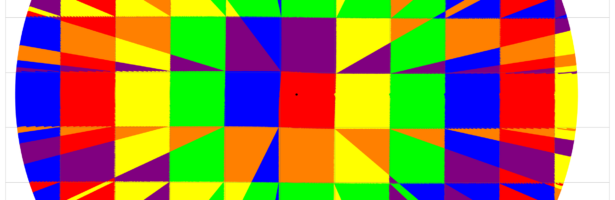

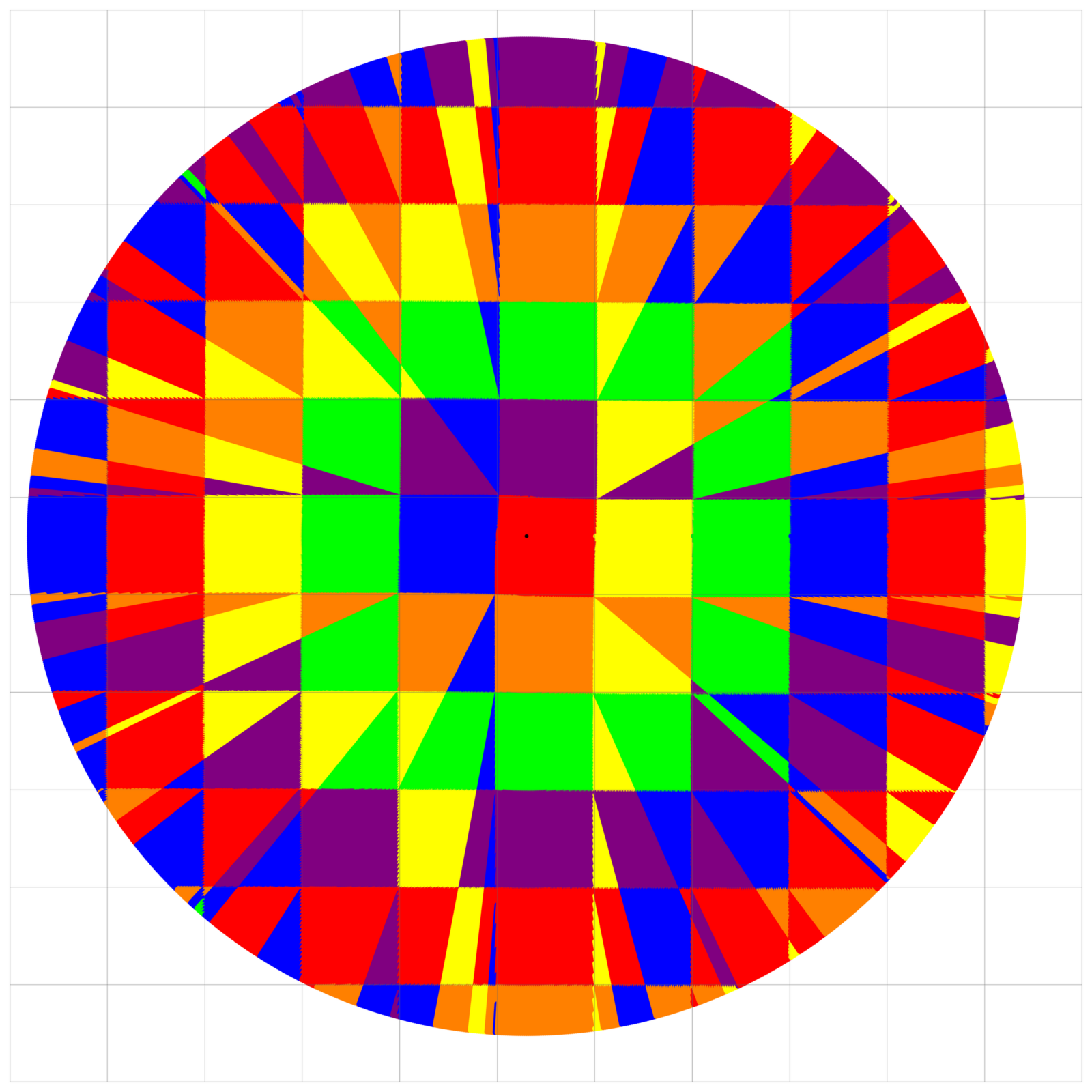

(or the empty word which is the identity,. Similarly as in any combinatorial group setting, the Cayley graph is assumed to be non-directed so that we can apply A or its inverse and count this as one letter. The god number of the Rubik cube for example is 20, but that is the story if we can turn a face by 90 or 270 degrees and count as a letter in the word). We can visualize the motion in the G-bundle of the cube by drawing the square on which the initial point is, then unfold this to the entire plane and then color a point on the circle

with the group element color of that point. Along the line segment going from P to X, the group element changes in a periodic or almost periodic matter; the group updates every time that an edge is crossed. The structure of the group

assigned to

is complicated. It is natural to conjecture that it is equi-distributed but it looks unexplored and unknown. Even if it were equi-distributed, we would need to show that is equi-distributes fast enough in order to see that the wave front is dense. This January, we made some attempts to write the proof of the density of wave front on the cube down more clearly. The idea is simple: we know that the wave front is dense on the torus: for

, the wave front on the torus

is

-dense there. We need to show that the wave front is dense also on the cube. What we can do is to take a point Q on the cube. It can be represented as a point

in the principle G-bundle on the torus. This is a fancy way to say that if we know the position of the point in a face of the cube and also know how the cube is oriented, then we know the point on the cube. The idea is now to move around on the cube by applying the group elements A or B and to verify that when we do that, we still have wave front elements nearby. Without loss of generality, we only need to see how that works when applying A (which can be thought of as the rotation about the y axis by 90 degrees if the face is the ground face). First take a wave front point

that is

close to

. This carries a group element

. If we look at the cube point that belongs to the adjacent face to the right, then this is

. Its projection on the torus is

but this point is not necessarily on the wave front. We have to move again a bit along the line PY without crossing a grid curve to get to a wave front point

that has the same group element

attached. We have now shown that within an

neighborhood of the point Q on the cube, there are wave front points with group

and with group

. Similarly, by doing the same with

or

or

we can reach points for which the group element has word length

. Doing the same thing

times shows that in an

neighborhood of

there are wave front points from all the 24 different group elements. We especially have wave fronts on each of the cube sides nearby. One of them matches the side in which

had been in. That is the proof. We know that for

, the wave front is

dense on the cube.

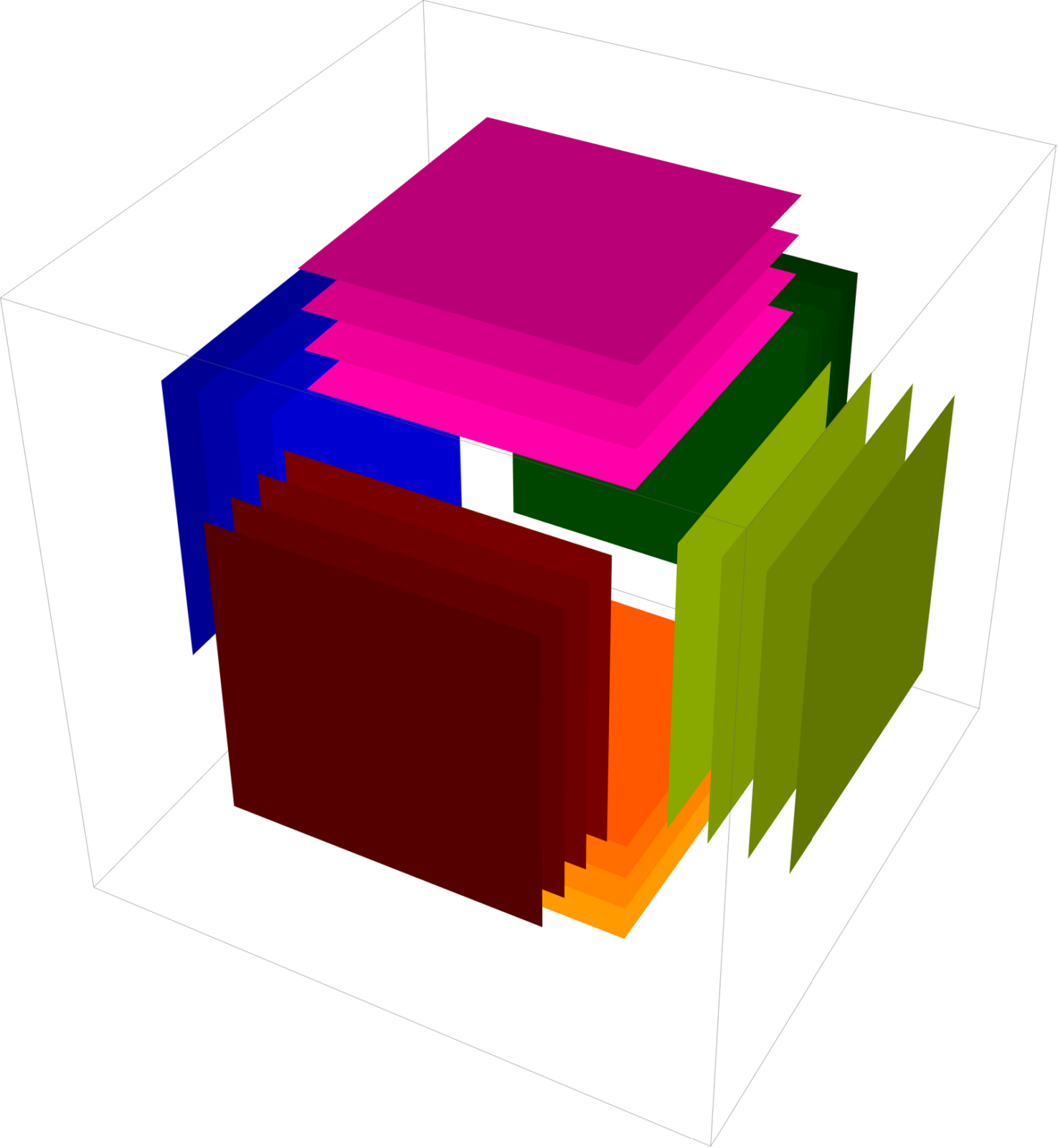

This story is interesting also because it ties in with basic building blocks of dynamical systems. As for every geodesic flow, this geodesic flow that is defined on a set in the tangent bundle

of the cube

. This set

carries a volume measure and the flow preserves this volume. Due to the nature of the cube, if the initial velocity

is given, it defines a vector in space and at each later time, this velocity vector is of the form

, where

is an element in the finite rotation group

that preserves the cube. In the smooth case, if

is the geodesic flow and

is a matrix valued Frenet curvature matrix describing the motion of the TNB frame attached to an orbit, then we have a cocycle

that has the property that

. In our case the curvature matrix is a distribution so that

remains in a finite subgroup of the rotation group

. The behavior of this cocycle is hard to predict because of the non-commutative nature. This is one of the major difficulties why Lyapunov exponents of dynamical systems in dimensions larger than 1 are so difficult. The cocycles are in a non-Abelian group. The Birkhoff ergodic theorem which allows just to compute expectations to get time averages does not work any more. It is replaced by a non-commutative version, the Oseledec theorem. But the outcome is very hard to compute. Even in the simplest situations like the standard map

on the 2-dimensional torus, where nobody has proven positive Lyapunov exponents on a set of positive measure for any value of c. One of the standard pictures of that game, (especially if the cocycle takes values in a finite group) is to look at the dynamics on the space $M \times G$ which in the case of the cube is the “translation surface” of the cube. It is the flat surface you get when unfolding along the orbits. We see the translation surface to the right.