A geometry is a space on which one has a derivative and notion of integration. This can be expressed more elegantly as a space with a cohomology as cohomology are kernels of matrices defined by the derivative and when looking at operators one needs a Hilbert space which intrinsically defines integration or summation. In many situations this is canonically and automatically given with the structure. The point of view of having the Dirac operator as a central object is pivotal for extending things to the noncommutative case. Non-commutative geometry had been “in vogue” when I was a graduate student and I mentioned it in my thesis from 1993. See also this youtube video about non-commutative space from early 2024.

Examples are:

- A simplicial complex G comes with an exterior derivative d on

. The uniform counting measure on G defines a trace and so integration.

- A delta set also comes with face maps which define an exterior derivative. It generalizes the special cases of simplicial complexes or simplicial sets (which are delta sets with more structure)

- A compact Riemannian manifold comes with a volume measure and so a Hilbert space and an exterior derivative d defining a Dirac operator D.

- A Connes spectral triple by definition has already D. In the finite commutative case, the algebra and the Hilbert space are the same.

- Cohomologies for higher characteristics are defined by a derivative on intersecting k-tuples of simplices. (see this document from 2018) or this from 2023)

- Decoupling the Dirac operator allows for more flexibility and even look for analogues of Atiyah-Singer or Atiyah-Bott in the finite.

A geometry so defines a natural metric structure with a distance given by the Connes distance formula. That formula is one of these quite rare “simple but powerful ideas” in mathematics which are usually not appreciated. An example of such an idea is the Fermat principle telling that for extrema we better have the derivative to be zero. Totally obvious but it is the key for the world as practically all important laws in physics and mathematics are based on variational or optimization principles. Fermat’s ideas apply to the bending of light at a surface, geodesics, the Einstein equations, mechanics, electromagnetism optics, statistical mechanics, you name the theory, and variational problems play a role. Even machine learning is base on this simple principle. If you are not maximal, just go in the direction of the gradient. Connes formula is in principle as simple as Fermats principle and turned out to be the key to push classical mathematical theories into the noncommutative. Sometimes, this is obvious: just replace a commutative algebra like C(X) with a non-commutative algebra like an operator algebra to some sort of quantization or to see von Neumann algebras as non-commutative geometry. The examples of seeing the theory of C* algebras as non-commutative topology or the theory of von Neumann algebras as non-commutative probability theory might be obvious, the push of Riemannian geometry into non-commnutative settings needed an original idea and the focus on the Dirac operator was genius.

[Added December 14th: I myself got heated up with this idea once I saw that a Jacobi matrix L can be factored as , where D is again a Jacobi matrix but over a doubled lattice. In the context of random operators, this step requires to double the underlying dynamical system with a 2:1 integral extension. This renormalization of dynamical systems is almost trivial and leads to a unique fixed point, the additing machine on the dyadic integers or von Neumann-Kakutani system as it is known in ergodic theory. The limiting operators of course by functional calculus will have spectra of the Julia set of c. (if c is complex, then the limiting operators of course are no more self-adjoint as their spectra are complex.) These operators are almost periodic matrices over the von Neumann Kakutani system. During my postdoc times, I once thought being able to prove that these operators have purely singular continuous spectrum for ALL x, and even talked about this once in Birmingham (Alabama) but I found after the talk a gap in the proof and I think the subject is still unsetttled.) I got later obsessed with renormalization of simplicial complexes which is of course just Barycentric refinement. The spectra of the Dirac operators then universally converge depending on the maximal dimension of the complex. Also this idea of “selfsimilarity” is rather basic but powerful and at the heart of fractal geometry or universality. It is clear where this all comes from: my phd dad Lanford had been the first to prove the existence of the Feigenbaum fixed point, a task so difficult that it had been first done computer assisted. The renormalization of dynamical systems or Jacobi matrices I had persued during my graduate school time is a piece of cake in comparison. ]

It is important in this frame work that one can deform the operator to change the distance. We want deformations that preserve coordinate independent structures like eigenvalue, trace or determinant. Isospectral deformations are nonlinear in general. We can have Dirac Schroedinger evolutions which are given by u’ = i D u and which defines a unitary with Q’ = i D Q so that Q(t) = exp(i D t). In the Heisenberg picture observables satisfy X’=[iD,X]. Lax saw that many integrable systems can be written in the form of a Lax pair D’=[B,D], where B is skew and depending on D. For the Toda system for example, one has a deformation of Jacobi matrices L, where . The Toda system deals with integers modulo n

or the integers

or natural numbers

. In November 2011 (a bit more than 14 years ago) I experimented first with the system D’ =[d-d*,D] where D=d+d* is the Dirac operator associated to the exterior derivative. I noticed that this system preserves exterior derivatives but that D develops a diagonal part so that D(t) = c(t) + c(t)* + m(t) where c(t) is again an exterior derivative. If we look at D(t) and look at Connes distance, then all stays the same, we just essentially change the coordinate system with a time dependent unitary Q(t). Not exciting yet.

The situation becomes interesting if one takes the fact seriously that solutions of the wave equation define also distances. Waves on 1-forms are of electromagnetic nature. If F is a 2-form that is exact F=dA, then dF=0 and d* F = j are called the Maxwell equations (they have been formulated awkwardly as 4 equations when separating space and time). We can gauge A by adding a gradient of a function f so that d* A =0. In absence of a current j, we then have d* F = d* d A = (d* d + d d*) A = L A =0 which reads that d’Alembert A is zero. In other words, the wave equation holds. The Maxwell equations more generally read as the Poisson equation L A = j so that the electro magnetic wave coming from the charge-current 4-vector j is just expressed using Green functions of the d’Alembert operator (the Laplacian in Lorentzian space time). If we split time from space and write the operator then the electro-magnetic potential A satisfies the wave equation

. In other words, the exterior derivative d in the geometry determines how fast waves do propagate. Making d smaller means by the Connes formula that space grows in size (if you make the measuring stick smaller objects get larger).

Now comes the combination. If we insist that waves come from an exterior derivative (an operator mapping k forms to (k+1) forms, like Maxwell describes, and if we deform the Dirac matrix to D(t) = c(t) + c(t)* + m(t), where m(t) is a block diagonal part, then under any free motion of the geometry in its symmetry, space expands. I called m(t) the “dark matter” part because it does “not matter” for light propagation. The expansion accelerates fast near t=0, where D(0) = d(t) + d(t)^*, similarly what one observes in the early universe (and explains with a Deus ex Machina explanation, meaning one does not explain it.) Whether letting the Dirac operator move freely in its symmetry space has any relation with cosmology of course is only speculation. As mathematicians we do not care. We describe systems independent on whether they have any relevance in the “real world”. We have much more room in mathematics to play. (Much of theoretical physics is mathematical in nature therefore, minus the requirement of rigor of course …) In mathematics have no problem to investigate Lie groups that do not appear in physics, we can do all physics on finite spaces, we have no problem to run planetary systems in a 2025 dimensional Euclidean space or even on any geometry: the interaction is determined by the Laplacian and so by the exterior derivative and so part of geometry. It is just a matter of whether our computer can handle it (it can!) We know however mathematically by Bertand’s theorem that except in dimension 3 (Newton) and -1 (Harmonic oscillator), we have no stability of the Kepler problem. See this handout from a Math 21a course (25 years ago we still covered the Kepler problem in multivariable calculus courses).

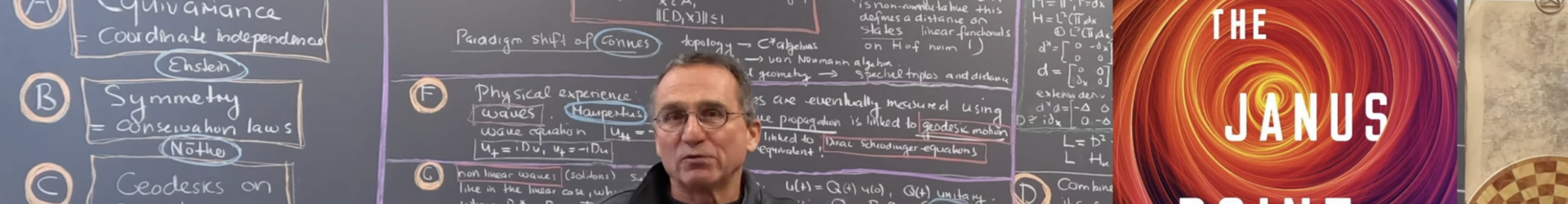

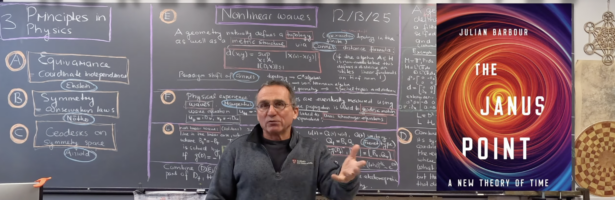

Anyhow, the subject is a great topic where various principles play a role. Here is a top 10 list for the current setup at least: one could add more, like the d’Alembert principle in the context of light or Schields principle in the context of geodesics (geodesic motion is free motion glued to the geometry, the A=QR decomposition is of this type. The Q is the part that is glued to the unitary group.

- Einstein principle: equivariance of physical laws. Of interest are only objects that do not depend on coordinate systems

- Noether principle: symmetries are related to conservation laws and Hamiltonian dynamics

- Arnold principle: integrable systems move on geodesic motion in the symmetry space of a system

- Lax principle: integrable systems are described by Lax pairs

- Connes principle: the Dirac matrix gives a notion of metric in very general situations

- Maxwell principle: the Maxwell equations dF=0,d*F=j of an exterior derivative d define light

- Haar principle: the probability to not to move in a continuous symmetry group is zero

- Romer principle: or determinism: the propagation speed of waves need to be finite.

- Huygens principle: light propagation is linked to geodesics in a space

- Dirac principle: take the square root of the Laplacian. Schroedinger and wave dynamics are the same.

I have pointed such things out before